Types of Programming Languages - Low Level vs High Level, Machine and Assembly, Procedural and Object Oriented, Compiler vs Interpreter

Hello. In this article, I am going to explain to you what the different types of programming languages are, why they exist, and how they relate to the way computers actually run your code. If you have ever looked at a program and wondered how a bunch of text turns into something that controls a rocket computer or even a smart TV, you are in the right place. I will walk you through the complete flow, from the lowest level bits that a CPU understands to the friendlier high level languages you and I write every day. Along the way, I will show you how procedural and object oriented styles are different, why we use compilers or interpreters, and how everything eventually becomes machine instructions. By the end, you will see the big picture clearly and know exactly where each idea fits.

What is a Programming Language?

A programming language is an artificial language designed to communicate instructions to a machine, particularly a computer. The word artificial here is key - unlike natural human languages that evolve organically, programming languages are intentionally designed by people to be precise, unambiguous, and executable by hardware or software systems. The whole point is to give a computer a step-by-step description of what to do.

Programming languages can be used to create programs that control the behavior of a machine. Think about everything from a rocket computer that needs timing-precise calculations to correct trajectory, to a smart TV that needs to respond to your remote, stream content, and render menus. In both cases, the behavior of the device is driven by instructions written in a language the system can eventually understand. The device does not improvise or guess - it executes exactly what the program tells it to do.

A program is nothing but a list of instructions written in a programming language that is used to control the behavior of a machine. If you imagine a recipe card in the kitchen, a program is like that recipe - but far more precise. Instead of saying cook until done, it would say set temperature to 180 degrees, wait 15 minutes, check internal sensor value, and proceed. That precision is what computers need. They follow the list in order, step by step, as if you were giving instructions to someone who only does exactly what is written.

There are many different programming languages, and as per the latest data, Java is one of the most popular languages that is being used for coding. Popularity shifts over time, but Java consistently shows up near the top in industry usage, teaching, and large-scale systems. When you hear that Java is widely used, it reflects the combined weight of enterprise systems, Android ecosystem history, and a huge community that trusts its tooling and reliability. This does not mean other languages are not used - it just highlights Java’s strong presence in the landscape.

Two Main Types of Languages: Low Level and High Level

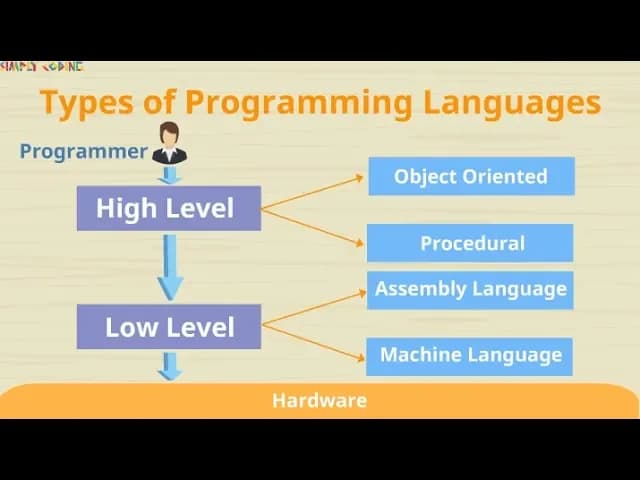

There are different types of languages, and the first big division is into two types: low level and high level. This split helps us talk about how close a language is to the hardware that ultimately runs the instructions.

Low level is a language which the machine understands directly or very closely. Low level languages are of two types: machine language and assembly language. These are close to the metal, which means you deal with the raw instructions the CPU can execute or with a thin layer of mnemonics that map almost 1-to-1 to those instructions.

High level languages are more user friendly and closer to human language. They are written in a syntax that feels more English-like and abstract away the gritty details of CPU registers, memory addresses, and hardware quirks. High level languages are also of two types: procedural and object oriented. We will learn more about each of them in order so that the flow makes sense.

Machine Language - The CPU’s Native Tongue

Machine language is the language which can directly run on the CPU. There is no translation step needed at runtime for the CPU to understand it because machine language is already in the exact numeric form the processor executes. When you hear people say binary, machine code, or opcodes, they are pointing to this same idea - the CPU expects sequences of bits and executes them as operations.

Machine language instructions are numeric, which means they are represented as a series of bits - zeros and ones - that encode both what to do and, often, the data or addresses to do it with. For example, one small pattern of bits could mean add the contents of register A to register B, while another pattern could mean jump to a different location in memory if a certain flag is set. Humans can learn to read these patterns, but it is extremely difficult to write meaningful programs directly in long strings of 0s and 1s.

This makes it tedious and error prone to write machine code manually. Imagine trying to implement even a simple loop or a set of conditional checks entirely by flipping bits, ensuring every address and constant is correct, and never mistyping a single 0 or 1. A single flipped bit can turn a harmless instruction into something that crashes the program. As programs grow large, the chance of making mistakes without any human-friendly notation skyrockets.

Machine language programs are not portable - a machine language is specific to a particular type of machine only. In practice, that means a binary compiled for one CPU architecture will not run on a different architecture. An instruction stream intended for x86 is not valid for MIPS, and vice versa. The way instructions are encoded depends on the processor design, so what makes sense to one CPU looks like nonsense to another.

Ultimately, all languages need to be translated to machine language. No matter how elegant or abstract your source code is, the computer must end up with the exact bits the CPU is wired to execute. Think of every compiler, interpreter, or virtual machine as part of a pipeline whose end goal is the same: produce correct machine instructions for the target hardware.

Assembly Language - Human-Readable Mnemonics for Machine Code

On top of machine language, we have assembly language. Assembly language helped eliminate much of the error prone and time consuming aspects of machine language programming by providing mnemonic codes for the corresponding machine instructions. Instead of writing 10110000 00000001, you write a short word that stands for the same instruction.

It replaces remembering zeros and ones with instructions which are mnemonic codes for corresponding machine language operations. For example, commands like MOV, JMP, CMP, and ADD read much more like tiny words than like raw bits, but under the hood they map directly to opcodes and fields the CPU understands. MOV typically means move data between registers or between memory and a register. JMP means jump to another instruction at a given address. CMP means compare two values and set flags accordingly. ADD means perform addition with registers or memory operands. Each of these still corresponds very closely to a single machine operation.

Assembly does not remove the need to think about hardware details, but it helps you avoid the most painful part of manipulating bits directly. You can use labels instead of fixed numeric addresses, write directives that help with data layout, and rely on an assembler tool to translate the mnemonics into exact binary. It is still low level, but far less error prone than hand-crafting bit patterns.

Each assembly language is specific to a particular computer architecture and sometimes to an operating system. That means there is x86 assembly, ARM assembly, MIPS assembly, and so on. Even within x86, you may encounter different assemblers and syntaxes. Examples include MIPS and NASM x86. MIPS refers to the architecture and its assembly language, widely used in teaching computer architecture because of its clean design. NASM is a popular assembler for the x86 family, which is common on desktops and servers. The syntax and tooling can vary, but the idea remains the same - mnemonics that map to the real instructions of that CPU.

High Level Languages - Portable and Closer to Human Language

Now let us take a look at high level languages, which are portable and whose statements are in English-like language, making them convenient to use. When you read high level code, you often see words like if, while, function, class, print, and names that describe what your data represents. This allows you to think in terms of the problem you are solving rather than in terms of registers and opcodes.

High level languages include C, Java, Python, and many others. Each of these gives you a friendlier way to express logic, structure programs, and manage data. You can write an algorithm once and, with the right compiler or runtime, run it on many machines without rewriting everything for each hardware type.

The amount of abstraction provided defines how high level a programming language is. Abstraction is about hiding complexity behind simpler constructs. For example, a for loop abstracts away the details of updating counters and jumping to instruction addresses. A string type abstracts away the messy details of memory buffers and terminators. The more a language hides low level details and provides clear, expressive building blocks, the higher level it feels.

Two High Level Styles: Procedural and Object Oriented

The high level languages are also of two types: procedural language and object oriented language. These are not different architectures like x86 or MIPS - they are different ways of organizing your program and thinking about how data and behavior relate.

Procedural Languages - Programs as a Sequence of Steps

In a procedural language, the program is written in terms of a sequence of steps to solve the problem. You break the task into procedures or functions and then call them in the order that makes sense. The flow is top to bottom, often with decisions and loops guiding the path, but still in a linear, step-wise mindset.

For example, think about steps given in a recipe. You start by gathering ingredients, then you chop, then you heat, then you combine, then you serve. Each step is clearly defined and follows from the previous one. If you wanted to express this procedurally, you would have functions like gatherIngredients, chopVegetables, heatPan, cook, and serveDish, and then you would call them in that order.

Or think about the sequence of steps you follow when you wake up. You might open your eyes, check the time, get out of bed, brush your teeth, make breakfast, and head out. In a procedural mindset, you would write a series of instructions that the program executes one after another, possibly branching based on conditions like if alarmSnoozed then goBackToSleep else continueMorningRoutine.

Procedural languages follow a top down approach with more focus on functions. You start from the overall task - what the program should achieve - and then break it down into smaller procedures. You pass data between these procedures, but your main mental model centers on what functions to call and in what sequence. This approach can be very clear for tasks that are naturally step-by-step.

Object Oriented Languages - Programs as Interacting Objects

In object oriented languages, the program is written as an interaction of functions between participating objects. Instead of starting from a big list of steps, you start by modeling the world: what are the entities involved, what data do they hold, and what actions can they perform. The behavior emerges from objects sending messages or calling methods on one another.

Let us bring back the morning schedule example, but now as objects. Imagine you have three objects: Eye, Fridge, and Microwave. Each of them maintains its own internal data and exposes some functions which others can use. The Eye might maintain data about light levels and sleepiness and expose functions like open and detectTime. The Fridge holds data about inventory and temperature and exposes functions like openDoor, getItem, and checkMilk. The Microwave tracks power level and remaining time and exposes functions like setTimer, start, and stop.

These objects perform their functions and interact to carry out the sequence of steps. When you wake up, the Eye opens and reports that it is morning. You go to the Fridge object to get breakfast items by calling getItem with parameters like eggs or milk. Then you ask the Microwave object to setTimer and start with a specific duration. You never directly manipulate the internal temperature variable of the Fridge or the internal countdown state of the Microwave - you call their exposed methods. That is the essence of object oriented thinking.

Object oriented languages follow a bottom up approach where there is more focus on data. You start by defining data types as classes, give them methods that operate on that data, and then compose bigger behaviors by having these objects talk to each other. The focus is on modeling real world entities and their interactions, rather than on a single global sequence of steps.

The disadvantage of procedural language is that data is not secure and code is interdependent, which makes reuse difficult. In many procedural designs, data might be global or widely shared, which can be changed by any part of the program. That can lead to hard-to-track bugs when one function accidentally modifies something another function depends on. Because many functions assume a particular shared data layout, pulling one function out to reuse elsewhere becomes harder. Code tends to be tightly coupled to the specific data structures and contexts it was originally written for.

Object oriented languages model the real world, so it is easier to relate to. When you map Eye, Fridge, and Microwave to objects, you write methods that feel like real actions and you keep internal details private. It helps in wrapping data and functions in a class, which helps build secure programs. This wrapping is often called encapsulation - the class hides its internal state and exposes only what others need to use. Code is modular and can be extended for reuse. You can take a class, add new behavior in a controlled way, and compose it with others without breaking the rest of the system.

How High Level Code Becomes Machine Instructions

A code in high level language needs a compiler or interpreter to convert the code into machine language. Remember, the CPU only runs machine instructions. High level source is for humans. So we need a translator that turns friendly syntax into the numeric opcodes a CPU will execute.

Let us understand the difference between the two. Both compilers and interpreters translate, but they do it differently and at different times in the development and execution process. Knowing the difference helps you predict performance, error reporting, and deployment behavior.

Compiler - Translate Ahead of Time and Produce an Executable

The compiler translates the high level instructions into a machine language and generates an executable file like .exe. This usually happens before you run the program. You feed the compiler your source files, it analyzes them, checks for errors, optimizes where possible, and then emits a binary file. That file contains the machine code the CPU will run directly.

With a compiler, you typically get error messages during the compilation phase if your code has syntax mistakes or type mismatches. Once compilation succeeds, you can distribute the resulting executable to run on machines with the same target architecture. The big benefit is that the code is already in machine language, so it often starts and runs quickly.

Interpreter - Translate and Execute Line by Line

An interpreter translates the high level instruction and executes each and every line individually. Instead of producing a stand-alone executable file ahead of time, the interpreter reads your source or an intermediate form, translates a piece, and immediately executes it. This read-translate-execute cycle happens repeatedly as the program runs.

Interpreters can be great for quick iteration because you can run code without a separate build step. They also make it easy to experiment line by line. The tradeoff is that translating on the fly can add overhead, and you usually distribute source or bytecode rather than a native .exe. The key idea remains exactly what we started with - one method translates to machine-level actions, but it does so incrementally as you go.

Wrapping Up and What Comes Next

You have just walked through the spectrum of programming languages from the lowest level bits to the higher level ways we write and organize code. We started with the definition of a programming language as an artificial language for instructing machines, looked at how programs control device behavior from rockets to smart TVs, and highlighted that Java is one of the most popular choices in use right now.

We divided languages into two big groups - low level and high level. On the low end, we saw machine language as pure binary and assembly language as human-friendly mnemonics like MOV, JMP, CMP, and ADD, with architecture-specific examples such as MIPS and NASM x86. On the high end, we looked at portability and English-like syntax in C, Java, and Python, and we separated high level styles into procedural and object oriented. We used everyday illustrations like recipes and morning routines to show how procedural steps differ from object interactions like Eye, Fridge, and Microwave working together.

We also connected the dots between your source code and the CPU by comparing compilers and interpreters. A compiler translates your code into machine language ahead of time and generates an executable like .exe. An interpreter translates and executes each line individually during runtime.

In our next video, we will learn more about object oriented concepts in Java. We will take the ideas we touched on here - wrapping data and functions in a class, making code secure and modular, and building systems that are easy to extend and reuse - and go deeper into how Java expresses them in real programs. Stay tuned for that deep dive.